BY ZII MASIYE

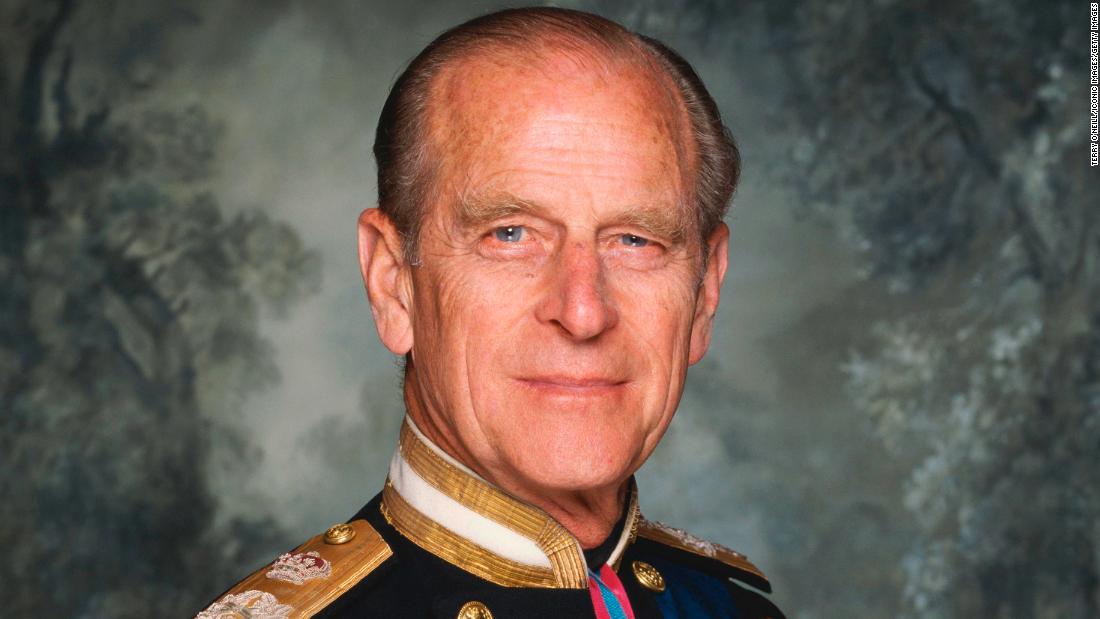

Prince Phillip is no longer in our midst. Some dark cloud seems to envelope Britain. May his soul rest in peace. A couple of weeks back, Southern Africa seemed to stand still under a similar dark cloud when isilo samabandla, Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekizulu, left us.

I am neither Zulu nor am I South African. Yet something of the death, as indeed something of the death of Chief Maduna of Godlwayo, torched something much deeper inside of me than would the death of some renowned political giant out here interred in the Heroes’ shrine.

Even in our thriving democracies, the true allegiances and ultimate abode of our African hearts lie with the traditional rather than the political or elective leadership of our times.

As the whole gripping ceremony unfolded, I thought what kept my eyes glued on the screen and my heart bleeding would have been the whole unique repertoire of nostalgic and traditional theatrics that accompany the death of a monarch.

The defiant stomping rhythm of the king`s regiment, the “Amabutho”, the sheer stature of those determined, huge men clad in amabhetshu moving in disciplined unison, singing and stomping in the cultured military fatigue and roaring war-cries reminiscent of that little-told Battle of Isandlwana. Their eyes steely and intent, their warrior arms brandishing their spears and ‘amahawu’, the King`s regiment embarrassed government authorities, sent Cyril Ramaphosa and SAPS scampering for cover, defied Covid-19 protocols would never leave sight of the body of their commander–in-chief, in death as in life.

I thought, like any other perverted male, it would have been the sensual assault of innocence conjured by stunning bare-breasted Zulu maidens prancing about, singing and dancing in their own beautifully provocative routines that would hold me prisoner to the funeral show of an arrogant, potentially homophobic, xenophobic charlatan of lavish tastes and outlandish controversies.

I was drawn too, by the shift in text, in syntax and discourse and the rich language and communication motifs that conveyed ceremony and the intrinsic power of the moment and that made pointers to the wealth of culture and history in the tangible and the intangible heritage of both citizens of Zulu origin and the peoples of Southern Africa in general. I felt that civilisation, “education” and the white men may have deliberately de-educated me, de-cultured me and ripped me off my essential cultural rooting as an African, perhaps rendering me a permanent mental slave of his ways. I felt somewhat naked, robbed of my rich history and culture. I felt embarrassed of our confused funerals and so-called white weddings.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Goodwill Zwelithini did not die like commoners do. No. But ilanga litshonile (the sun has set). A King doesn’t quite die like politicians. No. But inkosi ikhotheme, he bows. The King is not buried, but uyatshalwa.

I have had an inspired discussions with my grandchildren about these and implications or several similar euphemisms that accompany the life and death of African royalty. They are not just decorative euphemisms. They go deeper into locating the entire life-scape of umZulu’s primarily pivoting on the fulcrum of the monarch and kingship. The king is way bigger than the person of Goodwill Zwelithini. He is a timeless institution, the epicentre of being Zulu. The king is an epitome that singularly symbolises the natural elements and ecosystem that provides the tangible livelihoods and the cultural wellbeing and identity of his own nation—the land, the water, the air—perceived as prior and above the political sphere and political authority. The power and relevance of so omnipotent an institution in a people’s lives is such that it may never die—or cease. It is permanent. Like the sun, it may set, but only so as to rise again tomorrow. Like a seed, the King goes into the earth only to be planted.

I was left in awe as culturalists and historians of different orientation unravelled the primacy and historical wealth of KwaNongoma, the cultural cauldron and home of Isilo’s six palaces, the capital of the heroic Ndwandwe nation and the birthplace of my own king, uMzilikazi kaMashobana. I was intrigued by the chronicles of Nongoma, of Cetshwayo and the Battle of Mhlathuzwe, the warrior exploits of Zwide kaLanga.

The captivating tales, coupled with the sheer charm of the king’s coffin to attract so many people.. mourners of Zulu and non-Zulu extraction, excited interest and brought me to a deeper enquiry of who I really am and what the true place of traditional leadership could be in modern society—It brought me to a fresh realisation that in fact nothing is a greater social and economic fallacy than the pseudo-ethnic boundaries imposed on a homogeneous Basotho people straddling Southern Africa for his sole convenience by the white man who colonised us. It brought me to the fresh conclusion that, in fact, the poisoned pizza-pieces of degenerate minuscule countries devised by the Berlin Conference chefs that comprise the southern Africa pizza have no chance of ever realising their intrinsic competitive advantage in a ruthless global economy until someone confronts the dysfunctional evil of those boundaries.

It brought me to a fresh realisation that unless our conversation starts from deep within who we are as Africans, unless Africa reboots her factory settings and pursues a sincere understanding of herself from an internal perspective, our syllabus and curriculum are misaligned… We continue to dance the wrong song on an alien and oily dance floor… the evils of self-hate, division, conflict, poverty, underdevelopment and failure are yet with us for another century!

The strong sense of identity and pride of belonging, the voluntary desire for group loyalty and willing patriotism—all compelling conditions for unity, for collective purpose, visioning and effective nation- building could never derive half as well from any elected political leader as it does from a monarch, a king, a chief. By their very nature politicians must divide people. By their very nature, traditional leaders bind and unite people.

It became evident to me how the moral regeneration of the Zulu people and the attempts at pacifying tribal emotions that threatened to rip apart the entire governance fabric was courtesy of the king and the unifying force around traditional leadership since the bloody wars of IFP and ANC. Above all else the king’s brand was that of Peace Maker. In very deliberate ways, Goodwill Zwelithini had restored the cultural pride of the Zulu nation. His insistence on the revival of such traditional ceremonies as “Umkhosi Wokweshwamisa” boy-child circumcision, a youth rites passage designed to initiate and engender strong mores and principles that make men of integrity out of boys, are shining examples. Shaka mobilised men for military warfare. Zwelithini did the same for the war against Aids.

Multiple constructive conversations have arisen from “Umkhosi Womhlanga”, the Maiden Reed Dance that, in its own right, has shone an important spotlight on genderbased violence, the girl child and the roles and the pride of being an African woman. “Umkhosi Wesivivane”, an adult women rendezvous with the King that provides an important national platform for female dialogue around governance and what it is to be a Zulu woman. These and multiple initialises around land, the birthright and primary source of livelihood, defending territory, land ownership, agriculture, social integrity, cohesive co-existence, discipline are matters that hang in abeyance here in my country and in most of Africa that has allowed the relegation of traditional leadership to a governance dustbin or to control stooges of the state.