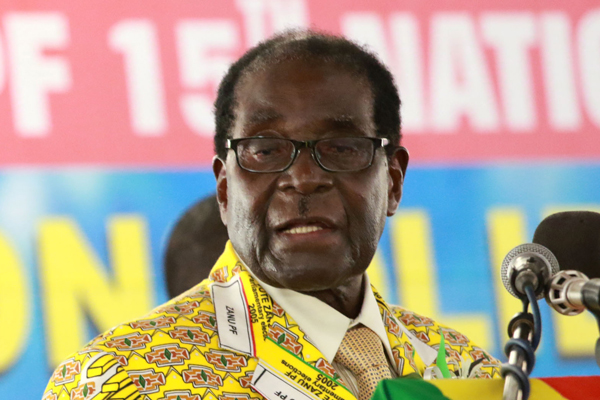

In January 1983, the government of President Robert Mugabe launched a massive security clampdown in Matabeleland and parts of Midlands, led by Fifth Brigade — a division of the Zimbabwean National Army.

guest opinion BY Hazel Cameron

This coincided with the imposition of a strict curfew in the region. Thousands of atrocities, including murders, mass physical torture and the burnings of property occurred in the ensuing six weeks.

Members of the unit told locals that they had been ordered to “wipe out the people in the area” and to “kill anything that was human”.

Mugabe named this North Korean trained unit “Gukurahundi Fifth Brigade”, a Shona term that loosely translates to the early rain that washes away the chaff before the spring rains.

The term Gukurahundi not only refers to Fifth Brigade, but also to the period of political and ethnic violence perpetrated by this unit in Zimbabwe between 1983 and 1985.

Gukurahundi resulted in huge losses for the Ndebele people of Matabeleland and parts of the Midlands.

The late Joshua Nkomo (leader of Zapu), in a letter to Mugabe dated June 7 1983, estimated that in the first six-week period of Gukurahundi, which commenced on January 20 1983, Fifth Brigade killed between 3 000 and 5 000 unarmed civilians in Matabeleland North.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The West German ambassador to Zimbabwe, Richard Ellerkmann, reported on March 11 1983 that “the churches’ estimate of total deaths, based on data collected from African sources, is about 3 000”.

Shari Eppel, Zimbabwean human rights advocate and forensic anthropologist, estimates the total number of unarmed civilians who died at the hands of Fifth Brigade throughout the entire Gukurahundi period to be “no fewer than 10 000 and no more than 20 000”.

Thousands more were beaten, tortured and raped.

The arbitrary arrests, detentions without charge, torture, summary executions and rape, suffered by the Ndebele, created an atmosphere of fear and mistrust, which persists to this day between the people of Matabeleland and the government of Zimbabwe.

This article illuminates the wilful blindness of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative British government between January and April 1983, when the Zimbabwean state-sponsored violence of Gukurahundi peaked.

The analysis of this study was undertaken through the prism of hitherto unavailable official British and US government communications pertaining to the Matabeleland massacres, obtained by Freedom of Information requests to various British government ministries and offices, and to the US Department of State.

This unique dataset provides minutes of meetings and other relevant communications between the British High Commission, Harare, the Prime Minister’s Office, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Cabinet Office and the Ministry of Defence, London, as well as the US Department of State and the US embassy in Harare.

The mining of such rich data permits a unique insight into the role of the British government in Gukurahundi and establishes: what information was available to the British government about the persistent and relentless atrocities taking place against the Ndebele people of Matabeleland North during the early part of 1983; what the British diplomatic approach was in response to this knowledge; and what the British government’s rationale was for such policies.

Importantly, this data is triangulated by analysis of the US declassified documents. It must be acknowledged that the documentary material considered in this study is not complete.

However, the 2 600 pages of documentation analysed, indicates that Robin Byatt, the British High Commissioner in Harare during the peak period of Gukurahundi violence, in addition to his diplomatic team and Major General Colin Shortis, the commander of the British Military Advisory Training Team, were consistent in their efforts to minimise the magnitude of Fifth Brigade atrocities.

It is indisputable that this is the general theme of the available cables that were forwarded from the British High Commission, Harare, to London during the period under study for this article.

Furthermore, this article will reveal that while both the UK and US were influenced by realpolitik, the US government demonstrated concern for the victims of Gukurahundi and placed a focus on the development of strategies and policies designed to challenge the state sponsored violence being perpetrated by Fifth Brigade so as to end the suffering of the black Ndebele people.

This was contrary to the approach of the UK government who wilfully turned a “blind eye” to the victims of these gross abuses.

Instead, the Zimbabweans who were of concern to the British government, and influenced their diplomatic approach, were the many white Zimbabweans living in the affected regions, and who were unaffected by the extreme violence of the Fifth Brigade.

The rationale for such naked realpolitik is multi-layered and expressed clearly in numerous communications between Harare and London.

This can be neatly summarised here by quoting a cable from the British High Commissioner, Harare, to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Geoffrey Howe, on June 24 1983.

He notes that: Zimbabwe is important to us primarily because of major British and western economic and strategic interests in southern Africa, and Zimbabwe’s pivotal position there.

Other important interests are investment (£800 million) and trade (£120 million exports in 1982), Lancaster House prestige, and the need to avoid a mass white exodus.

Zimbabwe offers scope to influence the outcome of the agonising South Africa problem; and is a bulwark against Soviet inroads.

Zimbabwe’s scale facilitates effective external influence on the outcome of the Zimbabwe experiment, despite occasional Zimbabwean perversity.

One can but assume that “occasional Zimbabwean perversity” refers to Gukurahundi and the summary killings and commonplace torture and rape of tens of thousands of Ndebele people.

This is an extract of a report that was recently published in the International History Review journal providing new information on the Gukurahundi atrocities.