By Farai Shawn Matiashe

HARARE — For more than a year, Lionda Mhonda searched for a plot of land to buy in northeastern Zimbabwe, but struggled to find anything that was both affordable and came with a legitimate title deed.

Then the 33-year-old farmer found out about a new app that listed not only land that was available for sale and lease, but also vital information such as legal documentation, crop history and average soil temperatures.

Two months later, Mhonda became a first-time landowner with an 80-hectare (198-acre) plot —quadruple the size she was originally looking for — near Marondera, about 70km outside of the capital Harare.

“At the time, I was looking for a plot with a long-term lease, but managed to find something even better — a plot that was available on a rent-to-buy basis,” she said. “This was a marvel at a good price.”

More than half of Zimbabwe’s irrigable land is lying idle, according to government data, but farmers say finding available land to buy or lease is a notoriously time-consuming and expensive process.

Launched in March, the Umojalands app aims to make the search for land easier and cheaper by letting farmers use their smartphones to find out everything they need to know about vacant plots around the country.

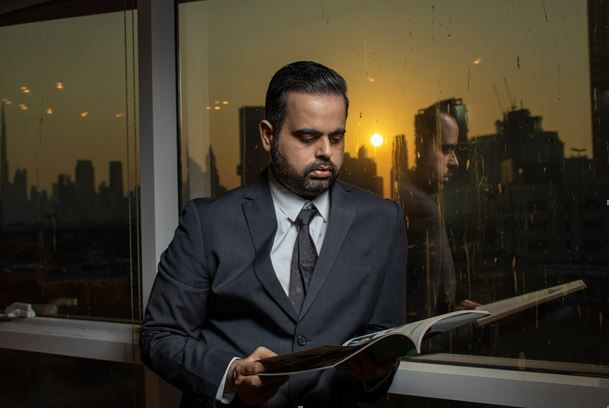

“Quite a number of young people in the country have potential in commercial agriculture, but they do not have access to land,” said the app’s creator Tafadzwanashe Gavi (27).

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

“Farm seekers can now access plots anytime, anywhere using their mobile phones,” he said, adding the app eliminates many of the costs that come with buying land, such as travel expenses, agent fees and due diligence costs.

Hitting the market just as the search for land was made even more difficult by travel restrictions due to the coronavirus pandemic, Gavi said the web-based app had already been downloaded by more than 200 people.

About 85% of the land in Zimbabwe is used for agricultural purposes, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

But land experts say most of that land is either underutilised or completely unused.

The auditor general’s report tabled in parliament in 2016 attributes the glut of unused agricultural land in Zimbabwe to mismanagement by the government and farmers, as well as poor infrastructure.

In a land reform programme launched in 2000, the administration of then-President Robert Mugabe started seizing 4,500 white-owned farms and redistributing them to low-income and landless black citizens.

“Most of the beneficiaries of land reform had no known experience in farming. A good majority had not even been trained on land use, let alone basic agriculture,” said Paul Zakariya, executive director of the Zimbabwe Farmers’ Union.

At the same time, he added, the impact of Zimbabwe’s worst economic crisis in a decade combined with recurring droughts meant even experienced farmers were struggling to use all of their land to its potential.

Government regulations say that farmers who want to lease land from the state through the land allocation programme usually first have to identify the plot they want and make sure it is unused before applying.

Umojalands co-founder Agatha Mandovha (23) said the app helps simplify the process of finding available land — whether state-owned or from a private landowner — and removes some of the obstacles that have led many farmers to abandon the industry.

“In choosing land, many factors are taken into consideration which need money and time, from soil type, weather patterns, crop history and available infrastructure to transport networks. We are addressing all that,” said Mandovha.

To find vacant plots, Gavi said he and his team look for social media posts from people putting their land up for sale or lease, and then reach out to them.

Sometimes, farmers approach him and ask to have their land listed on the app, which also records services for hiring tractors and drones for farming, he added.

Anyone using the app to look for land has to first show they plan to use it to help work towards building up food security in the country.

“We do not just compile details of a person who walks in randomly and says they want land. We request business proposals that include the amount of capital, the number of hectares, and the date the farming will start,” Gavi said.

“This will ensure that the farmer utilises the land to produce high-quality food (and) create employment for others.”

Lands deputy minister Douglas Karoro said that innovations like the Umojalands app could help boost the productivity of Zimbabwe’s underutilised land, which is high on the agenda for President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s administration.

The southern African nation, which was once the breadbasket of the continent, will import an estimated 1.1 million tonnes of grain in the 2020/2021 marketing year to meet demand, according to the FAO.

Nearly 8 million people, about half of Zimbabwe’s population, are food-insecure, according to the UN’s World Food Programme.

“The president is on record making it categorically clear that all land must be fully utilised so that we end hunger in our country,” Karoro said via WhatsApp. “Use of technology to identify underutilised land is most welcome.”

Olga Nhari, chairwoman of the Women in Agriculture Union, said the app could specifically help increase the number of women farmers around the country.

She noted that three-quarters of the union’s members are renting land and would benefit from being able to apply for state-allocated plots.

“The technology can surely save women farmers time, effort and resources. A woman will be able to get information on where exactly to go for available land, rather than blindly visiting various farms,” she said over WhatsApp.

“This technology will be a big, positive step for women farmers.”

— Thomson Reuters Foundation