TWENTY-four years ago on August 28 my father died. It was sudden, unexpected, shocking!

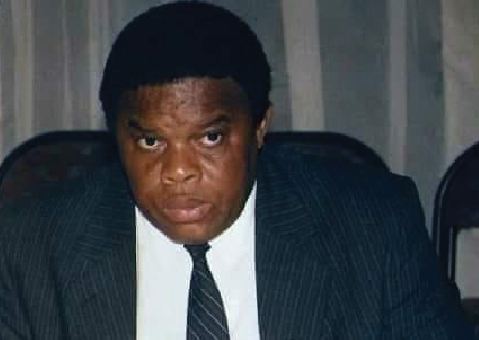

BY SIPHOSAMI MALUNGA

He had endured and survived much suffering in his lifetime. He had struggled to liberate our country and gone on to be one of the first nationalists incarcerated by the independent black government.

He was a larger-than-life individual. Indeed, my early memories were visiting him in prison at WhaWha.

It was a treat to be relished, coming as it did once every six or so months. He was loaded with contradiction as many of his generation are.

A brilliant yet complex and flawed man, who meant many things to many different people.

We have too many stories about him and his life that deserve to be in a book, which I have promised to write.

I know my brother Busi Mafuthengwe Malunga fancies himself a better scribe, so we shall see.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

As a politician, my father shunned the trappings of power. He resisted many generous offers of capture.

He died a poor man leaving what he feared more than death itself — some debt — he had said before that he would die from debt sooner than from an assassin.

It was not to be. He spoke truth to power inside and outside his political movement.

He berated and shamed his comrades when they strayed, and they did stray.

I have many stories about this. One includes how he was chased by Joshua Nkomo — who intended to administer his stick (induku) on him for ostensibly defying him regarding the elections in 1980.

Another is how he earned the nickname we gave him as his children — “Myopic”.

Seemingly oblivious to who he was talking to — he had gone into a tirade describing the people in government to my grandmother (his mother) as “myopic”, leaving us all shocked whether he seriously expected, let alone, intended her to understand what he meant by that word.

She had not gone to school and hardly understood such high-sounding “parliamentary vocabulary”.

A complete contradiction — he lived a very public life in public and a very reclusive life and in private.

He silently bore the scars of many years of prison and torture. In my older years, with education and some maturity, I have come to understand a lot more about him.

I have no medical basis for such a conclusion, but am convinced that he carried the burden of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Despite being free, he fortified his private space as if he was still in that [Ian] Smith or [Robert]Mugabe jail cell, coming out to fight for causes that he was ready to die for.

When, after his death, we cleared his office at the job he did as a public relations executive in Bulawayo, we found little to do with his work for the firm and correspondence from all over the country asking him to intervene in one way or another in righting some wrong or injustice.

A letter from an applicant for a teacher training post at Marymount Teachers’ College in Mutare, alleging unfair enrolment practice, a letter from an official in a parastatal outlining institutionalised corruption and asking him to “look” into it as the chairperson of Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee.

One story that I have never shared before, but which is probably pertinent for the contemporary times we live in, is of a time about a month or so before he died when we had a heated argument during lunch at Parliament.

I was a fourth-year law student at the University of Zimbabwe and steeped in student politics.

At one time I was captured on camera by ZTV during a demonstration, throwing stones at the police.

He had earlier tried to avoid criticising me for protesting, but had just casually said that “at times it’s okay to “lead” from behind.

I had torn into him, saying some struggles could only be led from the front.

On this particular lunch meeting at Parliament — I used to just “conveniently” rock up at lunch time with sometimes up to 10 comrades in the student struggle and we would all be “surprisingly” offered lunch — on this occasion, I was alone and the government had just announced a raft of increases in food prices.

Each time this had happened before, he would quickly condemn it in Parliament and talk about how it was hurting the poor the most, while corruption ran rampant.

This time, a week or so after the increase in prices, he had said nothing. So I confronted him over lunch about his silence “in the face of such hardship” for the poor.

I asked him whether he had noticed that the price of everything had gone up.

He responded dismissively that “he lived in the same country as me”. I then asked why he had said nothing about it.

His response was unusual. He said: “are people not buying the bread, milk and mealie-meal at the higher prices?” I responded that there were. He then said: “so on whose behalf am I expected to complain?”

The conversation ended there. I was defeated. Later, with experience and hindsight, the lesson hit home.

Citizens, not politicians, bear the ultimate responsibility. Here was a man who was considered the voice of the voiceless, man of the people, fighter for the poor, simply saying that his voice originated from none other than the people.

His authority derived from theirs and unless they took seriously their rights and responsibilities as citizens, he had no mandate.

A very apt point for all at our current political moment in Zimbabwe.

I always lived with the real fear that I would suddenly receive news of my father’s death.

Growing up in the 80s during Gukurahundi and seeing the harassment and torture he faced at the hands of state intelligence, he actually really lived longer than I thought he would.

From the late night or early morning raids at our house and his many arrests and detention incommunicado he taught us at an early age to be wary, cautious, suspicious, conscious of people around us — not fearful.

He never showed fear when men with guns came to pick him up at 3am — perhaps it was for us.

He would offer them tea, which I would rush to make as a way to stall them until it was daylight, but they would have none of it.

As they bundled him into a car leaving me and my little brother Kevin at the door, he would simply say, “I will be back soon”, when we all knew it could be the last time we were seeing him.

He would sometimes miraculously appear at the house in prison khakis with an “Osama-style beard” having persuaded his captors to let him visit his children.

He was many things, but bitter he was not. I could never understand how he was able to forgive and move on.

I recall the anguish he felt when barely a week or so after he was released (ostensibly to pave way for unity talks) from a three-year “unlawful” detention at Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison after he had been acquitted of treason, his father (my grandfather) died, but he could not attend the funeral because he had been tipped off that there could be an attempt on his life.

The task fell on my elder brother Busi to carry the spear. I wondered whether what was feared for my father might actually befall my brother instead.

The next few days were sombre and tense until my brother returned spear in hand; there were no mobile phones or Whatsapp those days to check- on him.

He seemed to understand that his fate was to fight and that of his friends in government to fight back.

At the end of it he maintained wonderful, yet uneasy friendships and relationships with comrades inside and outside government many of whom I still regard as my “fathers” and “uncles”.

I recall one time bumping into Eddison Zvobgo at his hotel in Masvingo years after my father’s death, and he was animated as he recounted story after story of my father the whole evening well into the night — I paid nothing — such was the contradiction.

There is so much to be said about my father, and, everywhere I go, I meet people who have countless wonderful stories about him. Perhaps his book should be actually be written by everyone. Despite my never venturing into politics — and having no desire to do so — many have drawn premature parallels between me and my father. Years of reckless living do mean I am now rounder and indeed bear a stronger physical resemblance. There is one thing that I can claim wholeheartedly to have inherited besides the looks. And this came intuitively from years of watching, teaching and learning. My father taught me to stand for what I believe in, to fight for justice wherever I am, to strive to contribute positively to society and never to fear anyone or anything that stands in the way of my beliefs or principles.

He taught me humility as I watched him sit on the floor at beer gardens talking to old men in the townships.

He showed me that political power is something to be unlocked and unleashed to improve the lives of people, and that where it failed to do so, it was to be looked squarely in the eye and challenged, questioned and corrected. That one man or woman can face an army and defeat it with principles and values.

That power fights back and does so with devastation. He taught me that a good and worthy death is better than a miserable and unworthy life.

He was the people’s hero but to me a father —flawed, contradictory, troubled but clear about his purpose on this earth — which I can safely look back at his life and confidently say he delivered on.

I can now only hope to fulfil mine.