The preliminary delimitation report done by the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec) and the attendant politics have highlighted three key issues peculiar to competitive authoritarian regimes that need to be identified and resolved ahead of 2023.

First is the capture of the electoral system by the ruling elite to influence the electoral outcome through gerrymandering, calculated to disorient the main opposition and benefit the ruling party.

These include collapsing of constituencies with more registered voters to beef-up constituencies with less registered voters and multiplying constituencies with Zanu PF majorities in Harare to list a few.

This paper gives an analysis of the Zec preliminary delimitation report to underline evidence of this.

Second is the elite discohesion within Zanu PF, which is identified as a precursor for a possible authoritarian breakdown.

This is shown through a sudden discohesion within Zec and between Zec and key allies of Mnangagwa affected by the preliminary delimitation.

Thirdly, Zec’s incompetence has been shown by failure to follow constitutional provisions, failure to follow simple arithmetic calculations to determine constituency and ward delimitation and the lack of consultation of key stakeholders.

Fundamentally, the botched delimitation report speaks to infighting within the ruling party elites.

- Zec failing to level playing field: CiCZ

- RG's Office frustrating urban voters: CCC

- Fast-track delimitation, Zec urged

- 'Political parties must not be registered'

Keep Reading

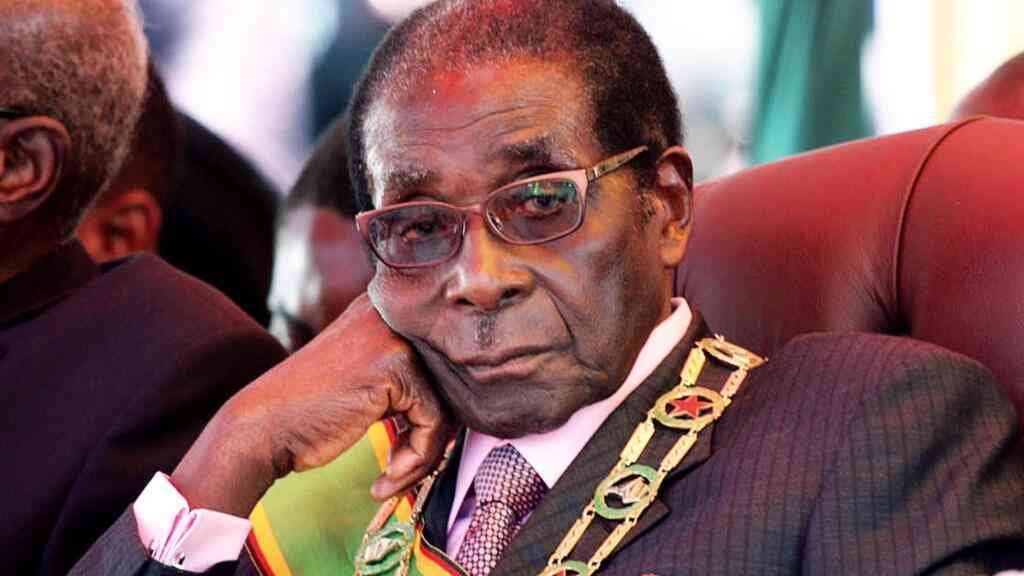

It is a continuation of the post-coup and post-2022 Zanu PF congress – the unresolved Zanu PF leadership question post-Mugabe.

Our view is that, the delimitation report generally and overall benefits Zanu PF as a political party but disadvantages one faction in the power matrix and configuration of the securocratic state.

The measure of the extent of democracy in the electoral process is provided for in Article 17 of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance read together with the Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa particularly article 4(a,b,e) which stipulates that:

Democratic elections should be conducted: a) freely and fairly;

- b) under democratic constitutions and in compliance with supportive legal instruments;

- e) by impartial, all-inclusive competent accountable electoral institutions staffed by well-trained personnel and equipped with adequate logistics;

The emphasis is placed on the need for Zec to conduct its delimitation process in a manner that is free, fair and in accordance with the constitution and by ‘well-trained personnel’.

In the constitution of Zimbabwe the delimitation process is stipulated in section 160 and 161.

For this paper, particular attention is given to section 161(6) which states that:

(6) In dividing Zimbabwe into wards and constituencies, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission must, in respect of any area, give due consideration to:

(a) its physical features;

(b) the means of communication within the area;

(c) the geographical distribution of registered voters;

(d) any community of interest as between registered voters;

(e) in the case of any delimitation after the first delimitation, existing electoral boundaries; and

(f) its population; and to give effect to these considerations, the Commission may depart from the requirement that constituencies and wards must have equal numbers of voters, but no constituency or ward of the local authority concerned may have more than 20% more or fewer registered voters than the other such constituencies or wards.

The law intended to balance two key principles of democratic elections applicable when doing delimitation.

First being to ensure numerical equality of constituencies and wards in terms of registered voters (section 161(3- 4)).

The second being to prevent gerrymandering or creation of constituencies with physical and geographic settings that make it difficult for voters to participate in a uniform manner (section 161(6)).

Thus the criteria to balance these two principles deduced from this section is that the number of voters in each constituency or ward can vary by up to 20% above or below the average.

This section 161(6) has been criticised for lack of clarity and explicit design of the formula to be used to calculate constituency and ward sizes.

In attempt to calculate the constituency and ward sizes, Zec has erroneously come up with constituencies that vary by up to 20% above and 20% below the average as explicitly stated in the preliminary delimitation report page 11 which states that: “In order to determine the voter population thresholds permissible in line with section 161(6) of the constitution, the total number of registered voters at the national level was divided by 210 constituencies resulting in a national average of 27 640 voters per constituency.

A 20% variance from the national average was then determined resulting in a maximum registered voter threshold of 33 169 and a minimum threshold of 22 112 voters.

Thus, any such constituency delimited was expected to fall within the minimum and maximum thresholds.

”As argued by Veritas (2023), constituencies that vary up to 20% above that average (33169) and 20% below the average (22112) have a difference of up to 40%, which contravenes section 161(6) of the constitution, and the Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa particularly Article 4(b).

To correct this error, the formula proposed by Veritas makes lots of sense.

Zec should have allowed constituencies to vary up-to 10% above the average (30 404) and 10% below (24 876) and make sure all constituencies range from 24876 to 30404 registered voters.

This will give them a 19% variation.

If Zec had widely consulted key stakeholders in Zimbabwe as stated in section 37(A) of the Electoral Act, this error could have been avoided.

Zimbabwe has been described as an ‘electoral authoritarian regime’ which holds regular and competitive multiparty elections while the electoral process systematically violates the basic principles governing democratic elections.

The lack of quality consultation was deliberate in order to simultaneously push and advance a factional position in the Zanu PF elite power struggles and disadvantage the opposition.

The report shows evidence of Zec’s gerrymandering done to benefit Zanu PF.

This is clearer when one looks at the constituencies affected by the erroneous delimitation.

Many constituencies delimited by Zec fall outside the permissible limits.

Gerrymandering strategies identified so far include: i) use of a wrong formula to calculate minimum and maximum number of registered voters to determine size of each constituency; and

- ii) inconsistent application of criteria used to determine the number of constituencies per province.

Use of a wrong formula For example, Binga North constituency has a total voter population of 8 1 118, which could create three constituencies with 27 039 voters, the registered voters according to Zec are 31307 which is above the maximum of 30404.

A logical explanation is that Binga North would have resulted in additional two constituencies created in an opposition stronghold.

Churu (33 001 voters), Harare South (32676) and Harare East (33 103) are well above the maximum (30 404).

What this error does is to under represent the Harare population while over representing others.

It can be argued that Zec sought to use this to avoid creation of additional constituencies in areas prone to be won by the opposition and the net outcome is the protection of Zanu PF majority in parliament.

In conclusion the Zec preliminary delimitation report confirms assertion that have been averred by the Zimbabwe Democracy Institute since 2012 that the independence of Zec is compromised by its strong links with the ruling party and the securocratic state complex and incompetent to handle democratic, free and fair election in Zimbabwe.

*This is an extract from a paper by the Zimbabwe Democracy Institute (ZDI) titled: Zec delimitation report: Electoral rigmarole and elite discohesion?