I try to write in such a way that I short-circuit, like in electricity, people’s traditions and morals.

Book Worm

Because only then can they start having original thoughts of their own.

I would like people to stop thinking in an institutionalised way.

If they stop thinking like that and look in a mirror, they will see how beautiful they are and see those impossibilities within themselves emotionally and intellectually – that’s why most of what I have written is always seen as being disruptive and destructive.

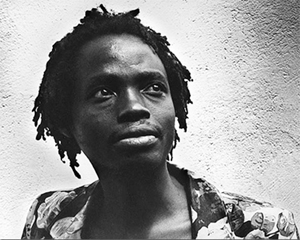

On August 18, 1987 Dambudzo Marechera died a lonely figure at Parirenyatwa Hospital to an Aids-related illness. Prior to his death, he had been living at Sloane Court in the Avenues district of Harare.

He was, at the time, as we now know in a hide and seek relationship with Flora Veit-Wild who made some startling revelations two years ago.

I first “met” Marechera in a school library at an out of way rural boarding school.

- In Conversation With Trevor: Justice Malala: Journalists are under siege

- Sambo launches third book

- In Conversation With Trevor: Justice Malala: Journalists are under siege

- Sambo launches third book

Keep Reading

I would sit behind colossal bookshelves, while my friends secretly groped their girlfriends, engross myself in the pages of The House of Hunger.

The book was a motion picture of my life experiences. I saw in it my grandparents, my parents and my contemporaries as we all fought the imperial powers of colonialism.

A supremely insightful observer who would have turned 62 this year, Marechera’s literary contributions speak across Zimbabwe’s great divides.

He avowedly embraced fellow writers with causes to fight for and who could also perceive a common humanity in their stories.

Those who appreciate Marechera’s acid won’t be disappointed with any smoothing over in his writings.

There are punches and uppercuts in his writings to institutions and figures who represent power in all its corrupting tendencies.

His legacy reminds us of our past, which also takes us forward. Marechera was one of the few individuals who did not have any faith in the independence project.

He was on the outside looking inside and exile in Britain had distanced him from the claustrophobic prisms of the “war vet” mentality that has been the ruin of Zimbabwe.

This easily made him a target of ‘hate’ and vicious criticism.

He rejected early on the black leadership in Zimbabwe, the same leadership responsible for the recent economic and political crisis today.

In 1978, at the height of the liberation struggle in Zimbabwe, Marechera is reported to have heckled when Robert Mugabe addressed his nationalist compatriots at the Africa Centre in London.

It is clear that he had no faith in the man who was to lead Zimbabwe into independence two years later.

He could see through his lust for power and his pretences to be “a man of the people.”

In fact, with the recent political crisis in Zimbabwe, Marechera specifically helps us to remember that all that glittered in 1980 was not gold. Warning lights flashed through his exuberant fiction; his challenging questions constantly provoked the authorities.

As Nadine Gordimer once remarked, Marechera stuck his neck out while others were reluctant to open their mouths.

The cracks in Zimbabwe were always there, only the heat of time was to deepen them. After the Lancaster House Agreement in 1978 and the landslide victory of Robert Mugabe’s Party (Zanu PF) in the 1980 elections, the sense of euphoria which followed was short-lived. Incidentally, the late Bob Marley who was invited to play at the independence gala composed a song titled Zimbabwe. Throughout the song Marley repeatedly warns the leadership that: So soon we’ll find out who is the real revolutionaries/And I don’t want my people to be tricked by mercenaries.

Even though Marechera lived to witness a country in transition, he recognised and condemned early on the contradictions of this artificial process. The euphoria for the newly reconstructed country was merely a façade behind which untold misery dominated. This resulted in Marechera being censured, insulted and sometimes imprisoned as recounted in the recent memoirs of David Caute, Marechera and the Colonel.

Marechera desperately advocated for freedom of expression and an environment that could encourage intellectuals and writers to play a critical part in the development of a new Zimbabwe without fomenting the kind of dogmatism that so often takes root. The dialogue between Grimknife Jr and Rix the Giant Cat in one of the untitled stories in Mindblast reflects this antagonism in post-independence Zimbabwe.

But when did Marechera become the writer he became? On leaving New College, Marechera entered a phase of his life in which he was permanently unemployed and had no settled home as he lived out the role of the “writer-tramp”.

There is no doubt that Marechera struggled to establish himself on leaving the “cloistered calm” of New College, Oxford. His time at Oxford had been somewhat detached from “real life,” he comments in The Black Insider, “I was just about to start a journey of discovery in the real United Kingdom.”

What little influence remained from the academic conditioning of his university experiences soon disappeared in his quest for a clear sense of identity and purpose.

The Black Insider demonstrates he was somewhat aware of the hybrid nature of his identity and his search was not so much a search of who he was, but who he might have been, had he not been subjected to the pernicious influences of colonialism. Bhukuworm@gmail.com